Auto journalist Ivan Berg reached his 89th year on March 31st. He’s been driving for 72 years and has owned an eclectic range of vehicles. He’s written several books about cars and was with BBC Top Gear magazine from its launch in 1993 until, as he says, he “sort-of retired” in 2010.

I got my driver’s license in 1953 and thought, wrongly, that it allowed me to drive on two wheels. So, of course, I had to have an Italian motor scooter. Vespas were all the rage, due to the movie Roman Holiday with Audrey Hepburn and Gregory Peck.

I bought a Lambretta to be different, and it had shaft drive. I bought the Mark II in 1958, and in 1960 I got involved with the then-new motorsport of kart racing. I needed to transport my kart to events in the UK, so I bought a Messerschmitt KR 200 Kabineroller, the three-wheeled cabin scooter that was designed by the aircraft engineer Fritz Fend, which factored into why I bought it.

I caused a bit of a stir when I transported my kart to events; I lashed it to the Messerschmitt’s luggage rack, thus making the combo almost undriveable. I eventually solved the problem, not by buying something a bit more sensible as a transporter, but by fitting a tow bar and trailing the kart on a specially-made trailer. (Another unique pairing.) At 40 mph on a bumpy road, the trailer was most often airborne.

The KR200 was also just the right size to act as a pace car, as seen in the above photo. It herded a troupe of Windmill Theatre showgirls for a rolling start in their first and only kart race (for publicity), with a large “FOLLOW ME” board fixed to the back.

I demonstrated skill as a racer, leading to a commission to write the first UK book about how to go kart racing, titled Tackle Karting this Way.

I joined the “cool” set in 1962 when I bought a green and white Morris Mini Cooper. Steve McQueen, The Beatles, Enzo Ferrari, Twiggy, David Bailey, Clint Eastwood, Peter Sellers et al … The Mini Cooper was and is an icon of the 1960s. That decade wouldn’t have swung nearly so swingingly without it.

Minis in green with white roofs were everywhere. I once watched in horror as my wife walked out of the post office and got into an identical Mini Cooper parked a couple of cars in front of me. I’m sure the driver was as surprised as she was.

But my Mini Cooper didn’t swing. It went through three gearboxes between 1962 and 1965. The last one lost syncromesh and I spent six months double-clutching and waiting for a replacement. Nevertheless, this skill came in handy when I raced in another Mini Cooper; I was able to keep the revs up when cornering. It became a habit, and I was a double-clutcher-cornerer thereafter.

Although my Cooper had a measly 55 hp, it didn’t weigh much, and it did handle something like a go-kart, the steering in particular. Changing direction was nudge rapid, helped with an appropriate dose of throttle. But in truth, I could never get it to oversteer anything like a rear-drive solid-axle kart.

In 1965, I exchanged the Mini Cooper for a Jaguar 2.4 MK II Auto. My wife, Inge, was Danish, and she hadn’t been home since 1961. She wanted to introduce our enchanting two-year-old daughter, Sanchia, to her Danish family. So off we went in 1966. Thirteen hundred miles. (Didn’t fancy that in the Mini Cooper.)

We thought the automatic Jag would be an easy, comfortable drive. And so it was. Two ferries, Dover to Calais and then Puttgarten at the top of Germany to Rodbyhavn at the bottom of Denmark. Eighteen hours non-stop. We stayed in Denmark for a fortnight, driving on remarkably well-kept and almost empty roads to visit relatives. And then, as we returned the same way we came, the Jag refused to do more than 70 mph on the Autobahn. Grace, Space… but no Pace! Apart from that, it was trouble-free on the journey. A world away from the thrashing Mini Cooper.

At a friend’s garage, the head came off. Why the poor pace? We had driven the whole way back on five cylinders. Piston number six was a mess. The engine had to be rebuilt, and the cost turned out to be more than the car was worth. At the time, I remember an American friend saying that in the U.S. it was legend that if you wanted a Jaguar, you had to buy two, because one of them would always be in the repair shop.

Inge enjoyed the Jag experience. Comfortable and quiet. So I bought a Rover 90. I hated it. This was a lumbering beast of a car. Underpowered, column-mounted gear-change. Yes, it was quiet, mainly because it was so slow.

I changed it for an MG Magnette ZB, and the enjoyment began again. Well, sort of.

The MG was relatively frisky after the Rover. It could do over 80 mph and took 23 seconds to 60 mph, which was quicker than the Mini Cooper’s 27. Rack-and-pinion steering, live axle on leaf springs. Drum brakes all around, so it didn’t stop very well. Nevertheless, it got me to the Scottish Highland resort of Aviemore, where I was a design consultant, several times without any significant problems.

Shortly after purchase, the starter motor packed up just when I was about to leave London. No problem—it had a starting handle clipped under the bonnet (hood). Ignition on. Insert starting handle. Half a turn and off we go. It was such a reliable way of starting the car that I didn’t bother replacing the starter motor until I sold it.

In 1970, I became employed in a new company that made educational audio-visual programs. It had a photography unit, and I decided it needed a camera car. I found a 1967 Series V Humber Super Snipe Estate in good condition and sent it to a specialist company that fitted it with a strong roof platform with tripod mounts and a ladder on the side for access.

It was a very big car. It looked a lot like the Chevrolet on which it was modeled. Six cylinders, inline, making 132 hp. It allegedly maxed out at 95 mph, but I never dared take it over 80. The power steering was incredibly vague. Gearshift was a column-mounted, three-speed manual with overdrive on second and third. Better brakes than the MG, thanks to front discs. It felt quick for its size.

We soon discovered that, although the car was fine for still photography, when we tried to run a film camera with the car moving, it proved useless. The car moved every which way, making filming impossible. That’s when I understood why most camera cars doing such jobs on race courses to follow the action were magic-carpet-ride Citroën DS Safaris with hydropneumatic all-wheel independent suspension. Oops.

In 1969, we took the Super Snipe on holiday to Denmark. The trip was uneventful. Then I took the car to the beach. I left the car park and drove onto the sand, closer to the sea. Then a bit more. And just a bit more. And the car was stuck. The sand was soft and deep. The heavy Humber wouldn’t move. Inge took an embarrassing set of photographs. Inge’s Dad negotiated with a group of fishermen sitting around drinking beer. A fresh crate of beer produced a helpful tractor.

I drove the Humber to Denmark once more in 1970. (I didn’t go close to the beach.) When we returned, I was fired from my video production job. I was given a month’s wages and my company car, a new-ish off-white Citroën GS. I don’t know what happened to the Humber.

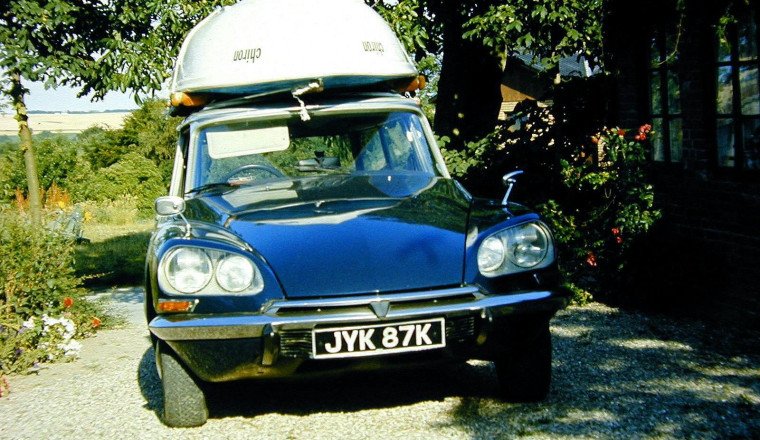

The GS was an interesting car. I had three of them between 1970 and 1982. But the Citroën I loved most was the 1972 DS Safari seven-seat Estate, which, apart from one of our regular summer tips to Denmark with a small sailing boat on the roof, once ferried six of us, plus luggage, from Ardelot (a beach resort south of Boulogne) to Hyères (in the South of France). The trip was non-stop and took 14 hours. It made it all the way back with a slipping clutch, too.

The DS was underpowered when loaded up, even though it had fuel injection. Four cylinders and three main bearings derived from the 1930s Traction-Avant, all serving up 130 hp; it was the only let-down in a car that looked as though it had dropped in from the future. Its suspension sighed and the car dropped when parked, rising again when started. There was a lever that raised the car high enough to change a wheel. It fascinated onlookers. It had a manual column gearshift, four gears, and disc brakes operated by a button where you thought a brake pedal should be. The button was very sensitive to pressure, leading to a few unwanted emergency stops until got used to it.

All versions of the DS are now regarded as collectible classics, with auction prices reaching $250,000 for elite examples of the luxury Chapron models. Not so the GS, examples of which have mostly rusted away, with very few cars still existing.

The Citroën GS had an air-cooled flat-four motor that loved to rev, and despite its measly 65 hp managed a maximum speed of 95 mph. It had the hydropneumatic suspension system from the DS and its aerodynamic body shape had a drag coefficient of 0.318. Very slippery for 1972.

It got the family safely home from Denmark one Christmas, after driving through thick, filthy fog in Germany’s Ruhr region. When we stopped for fuel, we discovered that we were leading a convoy of cars and lorries (trucks) that had also stopped and were waiting for us to lead them on!

The DS Safari was particularly prone to rust. After we had it for a year or so, Inge remarked upon a sloshing sound coming from the passenger side when the car accelerated or braked. Further investigation revealed that the door was full of water. The door drain holes became blocked due to rust, and when I cleared them, a gallon or more of rusty water came out.

Much as I loved the car, it had to go… for another Citroën in 1978. This time a red semi-automatic (that is, clutchless) GSA. I bought it new and specified a Webasto fold-back sunroof. And a tow-bar because I had a 14-foot sailboat on a trailer that I wanted to take with us to Denmark.

I regretted buying the semi-automatic transmission because I found the leisurely gearchange frustrating and a bit out of control, particularly for a double-clutcher like me. So when we got back from Denmark, I traded in for another GS, a white one.

I became a fan of the rotary engine in 1982 when my 12-year-old son Nik (now European Correspondent for this site) persuaded me to exchange the couple-of-months-old GS for a new blue Mazda RX-7. That eventually gave way to my only “supercar,” which is at least what Autocar magazine called it: a white RX-7 Turbo ll. Despite what the critics said about rotary reliability, neither car ever let me down over almost 20 years.

My most memorable drive was in the blue MK I, driving back from Aberdeen in the Scottish Highlands along the coast roads. It was a beautiful sunny day. Roads clear. Dire Straits blasting out on the cassette player and rotary engine howling at high revs. Sheer motoring bliss.

Forty years later, I drove another MK I, when Nik Berg discovered that Mazda UK had a blue MK I in its historic fleet and let us have it for the day in July 2022. You can read about it here.

I sort of retired, at the age of 73, from Top Gear magazine. That was in 2010. Inge had never been to England’s Lake District or the Scottish Highlands, so I bought an automatic racing green 2006 Jaguar S-Type with the 3.0-liter V-6 motor. Quiet, fast, and very comfortable. It had the Grace, Space, and Pace that Jaguar had promised but never convinced me of in 1962.

But we didn’t go touring, nor did we take the Jaguar on a trip to Denmark. Inge took ill and left us in 2014. I kept the Jag hoping it would eventually become a classic, until selling it in March of this year.

I left out the more run-of-the-mill Skoda Octavia. For family reasons, it replaced my Mazda Turbo II: RX-7 sports car = grandchildren not allowed. I had it from 2002 until 2010. The lively 1.8-liter Audi motor took us to Denmark several times in the noughties (aughts). The posh Laurent and Clement version, it was comfortable. The Great Belt Bridge was open and we took the 18-hour DFDS ferry from Harwich to Ejsberg in Denmark. Commodore Class cabin, a good restaurant, it was a luxurious mini cruise! And from there, Copenhagen was an easy three-hour drive.

Have a favorite from Ivan’s stable? Share it in the comments below, along with other favorite cars that have passed in and out of your care.

I like the Rx-7’s the best but this has been a pretty varied collection of cars, so lots to enjoy here.

Facebook Conversations