► 25 years on: remembering the Audi A2

► Design critic Stephen Bayley on landmark mini

► ‘There will never be a small car this clever again’

In the words of architect Heinrich Tessenow, ‘The best is always simple but the simple is not always the best.’

Take the Audi A2, 25 this year and still superb. In some versions it was capable of 94mpg and had the lowest drag of any production mini ever. Aluminium construction meant it weighed just 900kg. Yet it was a sales disaster, reaching only a quarter of the numbers of the contemporary (but in every way inferior) Mercedes A-class.

It’s an example of the German mastery not of efficiency itself, but the symbolism of it. All that sans serif public signage looks modern, but disguises systems of Kaiser-era antiquity. The deception is beautiful and mostly convincing. The A2 appears simple, but it is layered with layer after layer of meaning. Not really simple at all.

Because it was willed into existence by VW Group chairman Ferdinand Piëch himself, the A2 escaped Audi’s bureaucracy, bypassing all rational audits, eventually to lodge itself in our memory as one of the most exquisite small cars ever. Rational? Actually, not at all. And therein lies its wonder.

It is easy to say what went wrong. God, nature, call it what you will, drives a hard bargain. Aluminium has the benefit of lightness and corrodes less aggressively than many other metals. It is also a dream to recycle. But it is hard to work, requiring special tools and techniques. Insurance-company denials turned even minor A2 bump into write-offs. And then it was a death spiral.

Of course, this is like complaining you can’t put fine Limoges porcelain in the hot cycle of a dishwasher. Practical considerations are not important with works of art. Aluminium was an A2 article of faith: a demonstration of magnificent – but futile – corporate ambition. It was expensive and scared consumers, even as it left a residue of genius. It is a design masterpiece.

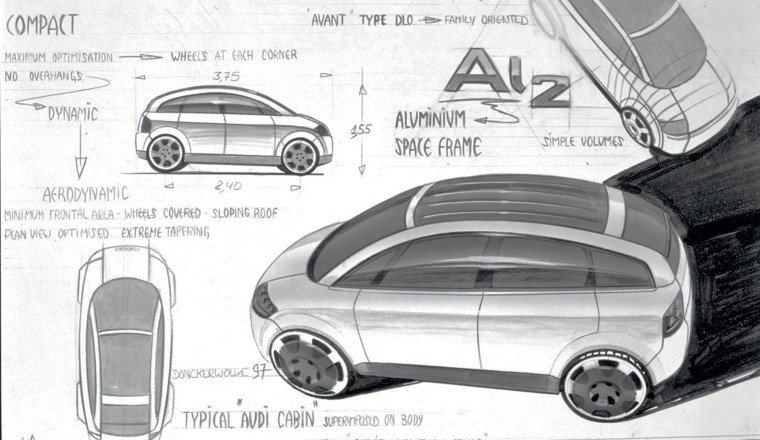

Attributing something as complex as a car to an individual is always problematic, but the Audi career chronologies of Luc Donckerwolke and Stefan Sielaff track the gestation period of the A2.

Whoever it was, the A2 designer fully acknowledged the significance of J Mays’ Avus concept of 1991. That car established a language of design for Audi that lasted until five or six years ago. From the Avus, the A2 derived superlatively confident, but plain, surfaces beneath which lurked historical ghosts. Plus, exquisite details.

These ghosts included experimental streamliners created by Paul Jaray, whose 1923 K-Typ Audi, like the A2, made no concessions to simplistic notions of elegance. In fact, it was pug ugly, but in a way that persuaded. In pursuit of the chimaera of ‘efficiency’, German designers often created some very peculiar-looking machines.

Blohm & Voss made an asymmetric aircraft. Anybody who has seen a Hanomag truck of circa 1969 knows the German aesthetic. A ’63 Unimog says the same: I don’t have to be kiss-me-quick cute to be impressive.

The thing about German design was this: while the Italians were, quite correctly, obsessed with bella figura, the serious business of looking good, Germans were obsessed by the serious business of trying to look serious.

Germans believed in systematic design. The belief was that following carefully considered principles, a good result was inevitable. This was a theory which paid no attention at all to divinely-inspired ‘creativity’, but it did give us Dieter Rams and his white and black boxes for Braun. And he, in turn, gave us Apple’s Jony Ive.

And in this region of design history we find the Audi A2. It is the iPod of the automobile.

The A2 may be a design masterpiece, but it is more specifically a German design masterpiece. The national pre-occupation with systems and efficiency can perhaps be traced back to medieval guilds and their insistence on specialisation: thus in Solingen you found cutlers, in Mainz watch makers. Factor in the dominant Prussian idea of military efficiency and you have all the forces – by no means all ‘rational’ – which let Audi flourish.

To be sure, the A2 is not a pretty car. That is like saying the Ossie athlete Katrin Krabbe was no beauty. But attractive and high-performance, certainly. Instead, the A2 speaks of seriousness. Of attention to detail, perhaps at the expense of attention to the larger picture. But we live with details, not with larger pictures.

Making judgements about this car is a treacherous business. It was a commercial calamity. It has admirers rather than lovers. And instead of looking into the future, it is not so much a car of the 21st century as a thing of a long lost and much regretted past.

But one thing is certain. No one will ever build a car quite like this again. As I write this, I am thinking of Brahms’ Deutsche Requiem.

Design critic, guru, cultural watchdog, occasional annoyer of Ron Dennis

Facebook Conversations