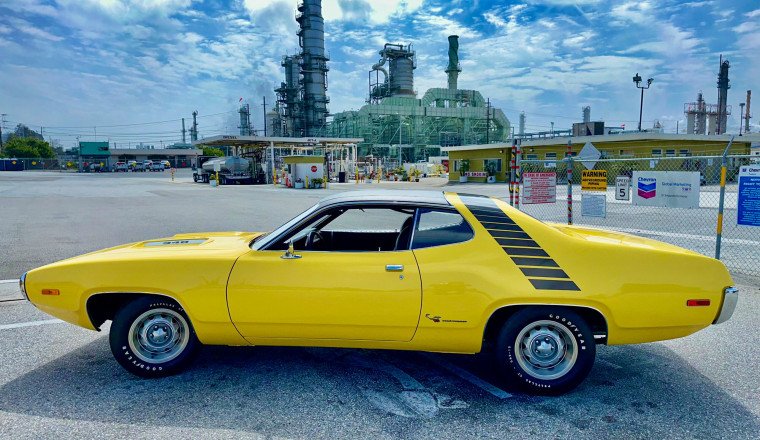

Sitting behind the wheel of his brand-new Plymouth Road Runner outside the Illinois Office of Secretary of State in Chicago in late September 1971, 16-year-old Victor Pineschi counted down the minutes to receiving his driver’s license. He watched as the examiner approached the car, his gaze down, toward his clipboard. (For Illinois drivers, this office serves as the Department of Motor Vehicles.)

The high school junior had just purchased the Road Runner with money he’d been earning from summer jobs since age 12. The Monroney sticker was still on the window. Likely alerted by the burble from the Road Runner’s dual chrome exhaust tips, the examiner finally noticed the bright yellow muscle car.

“He looked up from his clipboard, looked over the car, looked at me, and then he looked skyward like he was thinking, ‘Oh, my God,'” Pineschi recalls. “He got into the car and said, ‘Move forward.’ I put it into drive and moved up about 10 feet. Then he said, ‘Put it in reverse.’ I backed up about five feet. He said, ‘You pass.’”

The test Pineschi received was certainly not the standard Illinois driver’s exam. Not long before, while still on his learner’s permit, he had gotten into an accident while street-racing in his father’s Chrysler New Yorker. His dad, Ken, gave him hell but still let him buy a muscle car. He even phoned the district alderman (similar to a city councilman) to give his son some “insurance” when taking the test.

“If you had enough votes in your family, they would do things for you,” says Pineschi, a Los Angeles periodontist. He learned local politics from his father. “He called and said, ‘My son is coming to the Secretary of State for his driver’s license. Can you please take care of him?’”

They certainly did. License in hand and new Road Runner at his disposal, young Pineschi would do his share of tearing up the streets of Chicago. Painted Lemon Twist, the speedy Plymouth served as his regular driver for about 25 years. Today, the Bird occupies a special place in his small collection of muscle cars.

Pineschi treated his ’72 Road Runner to an amateur, partial restoration in the mid-1970s and early 1980s. He then had it professionally redone around 1990, doing some of the work himself. Through it all, the Road Runner, with 135,000 miles, has never needed its 340-cubic-inch V-8 or automatic transmission rebuilt. His meticulous maintenance, including changing the engine oil every 1000 miles, definitely helped. Except for replacement carpets and front seat upholstery, the interior remains original.

Pineschi knew exactly what kind of car he wanted when he was 15. He’d been heavily influenced by the muscle cars of Chicago’s street-racing scene.

“We used to meet under the Foster Avenue Beach viaduct in Chicago and watch the races,” he remembers.

Pineschi recalls the exact moment he fell in love with the 1971 Road Runner’s curvy new body style, which blended the roof into the quarter panels. He was on his way into downtown Chicago to see 2001: A Space Odyssey, the 1968 sci-fi classic that had just been re-released to theaters.

“I was standing on the Lake Street L train platform. Looking down at the street, I saw one. I thought it was the most beautiful body style I’d ever seen.”

He also knew how he would get one, because he’d been saving his money.

“I worked for my grandfather and uncle doing scut gofer work in construction during my summer breaks from age 12 to 16,” he says. “I spent one summer helping build a house for my uncle in Naples, Florida. I then worked for UPS as a loader for a summer and a bit longer.”

Pineschi says his work made him financially independent of his father at age 18, though his dad still paid his car insurance for a couple of years.

“It was because of me that he ended up in the assigned risk pool, and there was no way that any company would insure me,” Pineschi confesses.

The enterprising teen, meanwhile, had been a straight-A student. That’s one reason his father agreed to buy the car with the boy’s money and put it on his insurance policy. In mid-September 1971, they visited Gulf Mill Chrysler-Plymouth in Niles, Illinois. (The dealer is now Gulf Mill Ford.)

“There was a ’71 440 Six Pack still on the lot. That’s the car I wanted,” says Pineschi, referring to the Road Runner’s optional three-carburetor big-block engine. “My father said, ‘Absolutely not!’ but the salesman was savvy about getting the son what he wanted while placating the dad. He said, ‘Get him the small-engine one.’ That’s how I ended up with the 340.”

Following three years of showroom success, with nearly 175,000 sold, Plymouth’s budget muscle car entered 1971 wearing a curvy new “fuselage” body shared with the Satellite Sebring hardtop. At about $3200, the Road Runner was still an enticing value that included the 383 four-barrel V-8, dual exhaust, three-speed manual transmission, 3.23:1 rear axle ratio, and heavy-duty suspension and brakes. The Road Runner featured its own deep-set grille.

The new look tended to divide opinions in the Mopar community, though the Road Runner cartoon character persona, complete with a “beep-beep” horn licensed from Warner Bros., hadn’t lost its charm. You couldn’t blame the design for the Road Runner’s sales dive to just over 14,200 cars. Sky-high insurance rates for young drivers were killing the muscle car segment, and even Pontiac’s 1971 GTO barely cracked 10,000.

To address the issue, the Road Runner for the first time offered Chrysler’s high-performance 340-cu-in small-block V-8 as an option to help some buyers get lower insurance rates. The engine’s $67.35 upcharge over the 383 might have seemed counterintuitive—it was $1 more than the AM radio!—but about 1700 Road Runners chose it for 1971. The 440 Six Pack and the Hemi were still on the menu, though each one was rarely ordered.

The 340 returned for 1972 with a lower compression ratio (8.5:1 vs 10.25:1) and 1.88-inch intake valves versus the previous 2.02-inch ones. Because it was built in August 1971, Pineschi’s Road Runner 340 had a forged crankshaft; Chrysler switched to a cast crank in spring 1972.

A larger bore turned the 383 into a 400 for 1972, with lower compression. The industry’s changeover to SAE net horsepower ratings put the 400 at 255 hp and the 340 at 240 hp (down from 275). Performance was about equal for the two, and the 340 cut about 100 pounds from the car. (Chrysler had in previous years underrated the 340’s output, trying to fool the NHRA, but the un-fooled sanctioning body upped the rating to 310 hp.)

The Hemi and 440 Six Pack were gone for 1972, though the latter was still listed in the brochure and one such car was reportedly built. The 440 four-barrel from the discontinued GTX, with 280 net hp, became a Road Runner option, which when selected also put GTX badges back on the car. Just 10 percent of buyers took it. Despite the Road Runner’s still-strong performance and value, demand fell by nearly half to just 7628 cars. The 340 went into 2360 cars, 1839 of which had the automatic transmission.

Pineschi’s 1972 Road Runner was in stock and packaged with about $1000 in factory options. Oddly, the original window sticker did not break out individual option prices. Even stranger was a misprint that showed the 440 as standard. Pineschi’s car came with:

Original documentation shows the dealer discounted the $4327.65 sticker price to $3550. With taxes and fees, the Road Runner went home with Pineschi for $3826 (about $30,100 in 2025).

“It was not as fast as some of the other cars on the street, but the 340 was a good engine,” he recalls. He helped it with some Day Two mods, including headers and a Holley 650-cfm double pumper carburetor on a single-plane manifold.

“I remember going to Byron Dragway, and it ran consistent low-14s every time. With the 3.23 rear gearing, I needed the water to do a burnout but did not have to shift to do a second-gear burnout. I just sat on it in first. The car had no tach, but I didn’t float the valves or hurt the engine.”

Pineschi drove the Road Runner hard … sometimes too hard.

“I was a very responsible kid overall, but I was crazy with that car,” he says. “I got so many tickets, that one time my mother went with me to traffic court and showed the judge my report cards. That got me out of the ticket.”

One morning when he arrived home at 4 a.m. after a night out in the Road Runner with friends, he found his dad at the top of the steps just inside the house, waiting.

“He was a carpenter and usually got up at five to go to work. I quizzically asked, ‘Dad, why are you up?’ He said a policeman named Calabrese, who lived on the same block, had stopped by in the patrol car the night before and told him they’d been looking for me, and when they caught me street racing, they were going to throw me in jail. So, I just said, deadpan, ‘But Dad, they haven’t caught me yet.’ He jumped down from the landing in just two steps, but I was already out the door. Thank the Lord it was winter, and Dad did not have his shoes on. I didn’t come home for three days.”

The Road Runner accompanied Pineschi through college and dental school at Northwestern University.

“I drove the Road Runner to school every day and then work, even in terrible Chicago winters that often dipped below zero. I later had other beaters for more mundane tasks. It was parked outside most of its life, not garaged until the final restoration in the late 1980s.”

The Chicago winters had been nearly as tough on the car as its driver, so he gave it the first amateur restoration in 1973.

“I stripped the car, made it nice, painted it in my grandmother’s garage, and installed aftermarket wheels. It looked like a 9.5 when I was done, but I knew it wasn’t all correct.”

After earning his final advanced degree in 1983, Pineschi plotted the move to California to begin his career. He spent the six months leading up to that doing another restoration. In California, he continued using the Road Runner as a daily driver until the late 1980s, then retired it from that role and hired others to do a professional restoration.

“The trunk and floorpans never rusted, despite the Chicago winters for the first 12 years of its life,” he says. “The bottom of the quarters and fenders rusted, but not the door skins.”

He credits Mike Nowlen for doing “perfect” bodywork. “He was a very good friend and did six of my cars. He just died recently.”

Renowned Mopar restorer Bob Mosher did the final assembly, and his partial teardown of the engine confirmed a rebuild was not needed.

“There are no cracks on the dashpad,” Pineschi points out. “It didn’t get the sun like in the West. If I had not brought the car to LA, the vinyl roof would have stayed perfect, too.”

Pineschi credits George Grey for painting the car in the correct Mopar Lemon Twist enamel, with no clear coat. “He’s a guy who didn’t know any other word than perfection.”

Pineschi restored the grille, taillights, heater box, and some other items himself, and he collected other needed parts.

“Even things like the coil are correctly numbered and date-coded,” he says.

One part vexed him, however. During the restoration, he discovered the numbers on the radiator top tank matched a ’69 Barracuda. Sixteen years prior, he’d sent the radiator to a shop on Washington Street in Oak Park, Illinois to boil it out, so he concluded they unintentionally returned the wrong one.

“I had no idea what numbers-matching was in 1973. I started searching for the correct one, which was numbered only for a 1972 B-body 340 without air conditioning or power brakes.”

He scanned Hemmings classifieds for 14 years and finally found one in a batch offered by a radiator shop in Illinois that was closing.

“I called, but the owner had just sold the whole lot,” Pineschi recalls. “He said he would call the buyer and ask if I could buy just that one. A week later he phoned and said I could get it. I told him I just needed the top tank. He gave me the address to send the check, and it was on Washington Street in Oak Park. I might have bought back my original top tank 40 years later! I cannot verify that, but what are the odds?”

__

Car: 1972 Plymouth Road Runner

Owner: Victor Pineschi

Home: Los Angeles, California

Delivery Date: September 12, 1971

Miles on car: About 135,000

__

Are you the original owner of a classic car, or do you know someone who is? Send us a photo and a bit of background to tips@hagerty.com with ORIGINAL OWNER in the subject line—you might get featured in our next installment!

I used to be in those neighborhoods in Chicago back in the day. Good memories and a great car!

First gear burnouts are death for a Torqueflite, surprised he didn’t mention multiple transmission rebuilds in his story.

Beautiful car though.

My Torqueflite missed the memo, I guess.

Our family had the Satellite wagon version of this car. A 318 2V, Torqueflite, and manual disc brakes! It provided great service, although we had to add rear air shocks while on vacation to compensate for the rear end sag with a full load. Still love the chrome surround front bumper. One of the best looking ever.

I took drivers ED in a version of that body style.

Facebook Conversations